http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RhojA95e3Qc

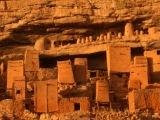

Here in Dogon country, a remote region of Mali in West Africa, after climbing a red rocky cliff and perching myself upon a 500 year-old cubical hut, I had an epiphany. As I watched the sun rise over the boundless plain below me, I felt like I could feel the sweep of history. After all, this is the terrain of the Dogon people, who over the course of the past millennium, have migrated, hidden and resisted slavery and religious conversion in order to preserve their rich cultural heritage. Fleeing from Islamic slave-raiders in the 18th century, they settled here along the face of the Bandiagara Escarpment, a massive red-rock cliff that marks the transition from high ground to plains. Originally settled by the Tellem, small hunters also known as “pygmies,” the cliff-face is still home to their ancient cubical dwellings. But despite its picturesque setting, life in this stark, dry land is quite difficult. Due to the constraints of limited land, low rainfall and increased population density, the Dogon people struggle for their own subsistence.

Fortunately, a few outsiders have helped the Dogon cause, starting with a French anthropologist that spent 25 years living amongst the Dogon, studying their rich cultural heritage and designing dams that have allowed them to develop the onion crop to supplement their subsistence. In recent years, a few of the larger Dogon villages have become popular with tourists, some of whom have started local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to help the Dogon’s health, agriculture and education; this is one of the positive examples of how responsible tourism can not only bring much-needed revenue to a stressed population, but also provide assistance to help improve the standard of living of this remote region’s inhabitants.

One of the biggest needs that must be addressed is the lack of educational resources. Due to their poverty and isolation the Dogon receive very minimal federal funding for their schools. In many villages, there is no government school at all, which forces local children to hike very long distances to receive a basic education. In some cases, community schools have been established, but as can be expected, such schools have very little in terms of funding and/or supplies.

On behalf of 100 Friends, I purchased $600 worth of desperately-needed school supplies to deliver to two remote villages here in Dogon country. Buying the schoolbooks in the closest city proved to be the easy part; the real challenge was transporting the boxes of supplies through the mountains and into the hands of the kids themselves. For three days, aided by a guide, a porter and a cow, I trekked this rugged terrain, visiting local markets, tribal dignitaries and ritual dances along the way. When the day’s trek was complete and the couscous with chewy chicken had been consumed, we slept under the stars while bracing the harmattan winds that blew sand into every crevice from the Sahara in the north.

We delivered half of the supplies to Begnimato, where a village elder, the headmaster and local teachers expressed their heartfelt thank yous, assuring me this contribution would definitely make a difference for these childrens’ education. As they told me, without the notebooks, pens, and miniature chalkboards the younger kids use to practice their writing, school lessons were confined to basic lectures, with teachers merely pointing to letters and words on the big chalkboard; starting today however, the students will be able to learn to write with their own two hands! For a writer such as myself, this is obviously a rewarding thought.

Upon arrival in the remote cliff top of Indelou, one of the most sacred animist Dogon villages, I was told the sad story about the German traveller who had heroically financed the construction of a school here, but was killed in a car accident on his way home. In order to carry forward his giving spirit, I decided to donate half of the notebooks, pens, chalkboards, etc. to the school, which though well-constructed, is practically empty of school supplies.

When the village chief, whose age can only be estimated to be around 85, blessed me for my efforts, I felt humbled in his presence, as he seemed to exude the wisdom of the ages. I conveyed my respect for his culture, particularly the importance placed on harmony, which is expressed in everything from the extremely-elaborate system of greetings to the architectural design of the toguna, the local “courthouse” where the men gather to settle local disputes; the low-hanging structure prevents angry outbursts, as anyone that stands suddenly will hit his head on the 3-foot high roof. (I only wish such a novel idea would be instituted elsewhere).

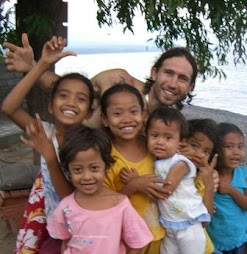

With all of our “advances” in the West, it is reassuring to witness firsthand a traditional culture that has struck such a fine balance between their environment and their daily lives. Sure, by our standards, the Dogon people are poor, but watching their masked dances weave through their villages, seeing kids trailing with big smiles and speaking to tribal leaders about their sacred animist rituals, I developed a deep respect for their cultural cohesion over the test of time.

As I look out on the sweeping plain below me, I think back to a simpler time, before the advent of the technologies we take for granted today. Perched here atop a mud brick house 200 feet up amidst the cliff, I bask in the knowledge that daily life here has continued nearly unchanged – talk about cultural continuity! Though their traditional culture persists, educational advances are imperative, as it has been shown how even an elementary education amongst African agriculturalists leads to more effective farming techniques, crop output and ultimately, family income. Surely, our investment in these two communities’ schools will help the Dogon people here improve their lives while retaining their rich cultural tradition, as it is an important piece of the globe’s cultural fabric, too valuable to be lost in the face of mono-culturation and lack of opportunity.

Here in Dogon country, a remote region of Mali in West Africa, after climbing a red rocky cliff and perching myself upon a 500 year-old cubical hut, I had an epiphany. As I watched the sun rise over the boundless plain below me, I felt like I could feel the sweep of history. After all, this is the terrain of the Dogon people, who over the course of the past millennium, have migrated, hidden and resisted slavery and religious conversion in order to preserve their rich cultural heritage. Fleeing from Islamic slave-raiders in the 18th century, they settled here along the face of the Bandiagara Escarpment, a massive red-rock cliff that marks the transition from high ground to plains. Originally settled by the Tellem, small hunters also known as “pygmies,” the cliff-face is still home to their ancient cubical dwellings. But despite its picturesque setting, life in this stark, dry land is quite difficult. Due to the constraints of limited land, low rainfall and increased population density, the Dogon people struggle for their own subsistence.

Fortunately, a few outsiders have helped the Dogon cause, starting with a French anthropologist that spent 25 years living amongst the Dogon, studying their rich cultural heritage and designing dams that have allowed them to develop the onion crop to supplement their subsistence. In recent years, a few of the larger Dogon villages have become popular with tourists, some of whom have started local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to help the Dogon’s health, agriculture and education; this is one of the positive examples of how responsible tourism can not only bring much-needed revenue to a stressed population, but also provide assistance to help improve the standard of living of this remote region’s inhabitants.

One of the biggest needs that must be addressed is the lack of educational resources. Due to their poverty and isolation the Dogon receive very minimal federal funding for their schools. In many villages, there is no government school at all, which forces local children to hike very long distances to receive a basic education. In some cases, community schools have been established, but as can be expected, such schools have very little in terms of funding and/or supplies.

On behalf of 100 Friends, I purchased $600 worth of desperately-needed school supplies to deliver to two remote villages here in Dogon country. Buying the schoolbooks in the closest city proved to be the easy part; the real challenge was transporting the boxes of supplies through the mountains and into the hands of the kids themselves. For three days, aided by a guide, a porter and a cow, I trekked this rugged terrain, visiting local markets, tribal dignitaries and ritual dances along the way. When the day’s trek was complete and the couscous with chewy chicken had been consumed, we slept under the stars while bracing the harmattan winds that blew sand into every crevice from the Sahara in the north.

We delivered half of the supplies to Begnimato, where a village elder, the headmaster and local teachers expressed their heartfelt thank yous, assuring me this contribution would definitely make a difference for these childrens’ education. As they told me, without the notebooks, pens, and miniature chalkboards the younger kids use to practice their writing, school lessons were confined to basic lectures, with teachers merely pointing to letters and words on the big chalkboard; starting today however, the students will be able to learn to write with their own two hands! For a writer such as myself, this is obviously a rewarding thought.

Upon arrival in the remote cliff top of Indelou, one of the most sacred animist Dogon villages, I was told the sad story about the German traveller who had heroically financed the construction of a school here, but was killed in a car accident on his way home. In order to carry forward his giving spirit, I decided to donate half of the notebooks, pens, chalkboards, etc. to the school, which though well-constructed, is practically empty of school supplies.

When the village chief, whose age can only be estimated to be around 85, blessed me for my efforts, I felt humbled in his presence, as he seemed to exude the wisdom of the ages. I conveyed my respect for his culture, particularly the importance placed on harmony, which is expressed in everything from the extremely-elaborate system of greetings to the architectural design of the toguna, the local “courthouse” where the men gather to settle local disputes; the low-hanging structure prevents angry outbursts, as anyone that stands suddenly will hit his head on the 3-foot high roof. (I only wish such a novel idea would be instituted elsewhere).

With all of our “advances” in the West, it is reassuring to witness firsthand a traditional culture that has struck such a fine balance between their environment and their daily lives. Sure, by our standards, the Dogon people are poor, but watching their masked dances weave through their villages, seeing kids trailing with big smiles and speaking to tribal leaders about their sacred animist rituals, I developed a deep respect for their cultural cohesion over the test of time.

As I look out on the sweeping plain below me, I think back to a simpler time, before the advent of the technologies we take for granted today. Perched here atop a mud brick house 200 feet up amidst the cliff, I bask in the knowledge that daily life here has continued nearly unchanged – talk about cultural continuity! Though their traditional culture persists, educational advances are imperative, as it has been shown how even an elementary education amongst African agriculturalists leads to more effective farming techniques, crop output and ultimately, family income. Surely, our investment in these two communities’ schools will help the Dogon people here improve their lives while retaining their rich cultural tradition, as it is an important piece of the globe’s cultural fabric, too valuable to be lost in the face of mono-culturation and lack of opportunity.

1 comment:

Great article Adam. Very informative and descriptive. I look forward to reading more of your posts and following along in your travels.

Post a Comment