With the stark threat of global warming closing in on us, current talk regarding the Amazon focuses on environmental issues. While it is true that the degradation of the region is already taking a punishing toll on the Earth´s delicate natural balance, this universalistic approach overlooks the hundreds of communities that inhabit the Amazon and the day-to-day struggle for survival they currently face.

Despite the common perception, most inhabitants of the Amazon are not native tribesmen. Sure, there are still thousands of indigenous people living deep within the sprawling 150,000 square mile of rain forest, but only the most remote tribes are safe from the peril of government interference, Christian missionaries or commercial loggers. In their case, isolation is their only hope for maintaining their cultural traditions and guaranteeing their survival.

Most outsiders ares surprised to learn that over 60 percent of the Amazon´s population are urban dwellers. Walking through cosmopolitan cities such as Manaus with over its million inhabitants, the only hint of the rain forest´s proximity is the humid, rainy weather and the plethora of exotic fruits being sold on the street.

Some of the most marginalized communities of the Amazon are the rural caboclo communities that are made up of descendants of indigenous peoples. One region of particular fragility is in the western portion of the enormous Pará state of Brazil, on the banks of the Arapiuns and Tapajós Rivers. The communities here, which range in size from 5 to 70 families, rely on fishing, subsistence farming and gathering for subsistence, but they are currently struggling for survival due to the rapid depletion of their natural resources, due to commercial fishing, slash-and-burn agriculture, emigration from other parts of Brazil and the expansion of commercial farms (which are fueling Brazil´s resource boom in corn, sugar and beef).

With this focus in mind, I explored the region in search of efficiently-run locally-based projects that address the major needs these people face: health, income generation, sanitation and education. By immersing myself in these communities, living, eating and sleeping by their side, I was exposed to the major challenges they face and discovered (and financially assisted) several amazing projects which positively impact theses people´s fragile existence.

HEALTH

Due to their geographic isolation, most of these communities lack access to medical doctors and hospital care, which presents a slew of health-related challenges. For starters, child mortality is very high; over 5% of babies don´t live to see their first birthday and 15% of deaths in these communities are children under the age of one. Another startling reality is the rash of easily-preventable diseases such as dengue fever and diarrhea, which are often fatal here if not treated. Without doctors to visit, kids never learn how to brush their teeth, mothers receive no pre-natal care and families are unaware of the importance of washing their hands and keeping their food free from contamination. Fortunately, an incredibly-run project called

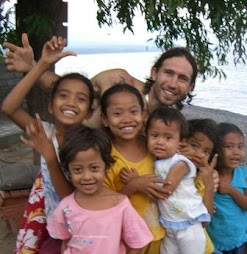

Health & Happiness sponsors a floating hospital that makes monthly visits to about thirty of these communities, with the doctors, dentists and surgeons on board providing their services free-of-charge to the local residents. Miraculously, they have cut child mortality rates in half and have dractically improved the overall health of these communities in the last decade. In addition to medical services, Health & Happiness also performs a circus in each community, using this clown-filled approach to help spread their health tips. I was lucky enough to witness one such performance and while painting the kids´ faces – their eyes lit up with such brilliance – I could tell that some of these kids had never participated in such an exciting spectacle. While helping administer a tooth-brushing workshop (full of plaque-themed songs and games) for the children, it warmed my heart to see these kids learning such an integral skill and having so much fun doing so. The $570 I have donated will help finance this incredible project and will go towards the pruchase of much-needed medical supplies (and a few toothbrushes as well).

INCOME-GENERATION

Since the vast majority of land in this particular region of the Amazon is federally-protected, the caboclo communities are not allowed to farm for profit. Cultivation is limited to subsistence levels and carried out in a communal manner. As a result, the people rely on alternative forms of income generation. By providing a means of income to these communities, we can assure they will not resort to degrading the rainforest to ensure their own survival. I encountered some projects that promote the production and sale of traditional artesanato handicrafts, and others with an environmental focus, such as a federally-funded turtle farm that sells turtle meat and helps protect the species´ survival by guarding their breeding ground and releasing healthy turtles into the river.

While staying in a community called Cachoeira de Aruá, I encountered a recently-founded furniture construction project that provides employment for local residents, income for the community and preservation of the local environment. Local men are taught how to construct furniture (beds, wardrobes, tables, chairs, etc.) while also facilitating local conservation efforts. They take inventories of the area´s tree species and extract wood in an environmentally-sustainable manner. [A large plot of land is divided into twenty quadrants and wood is extracted from only one quadrant per year so that each plot is given two decades to regenerate itself before any logging takes place.] As of now, the workshop produces furniture for local communities, spreading the income amongst their families with 30% going towards a communal resource fund. Our goal is to supplement their income by expanding their reach to all of Brazil by working in tandem with an on-line market that has been established to help such projects (

http://www.mercadoamazonia.org/). Speaking with the Director of the project – himself an expert woodcrafter and experienced development project manager – I learned the major impediment to expanding their market is the humidity here, as wet wood is nearly impossible to work with. In order to address this hindrance, I have donated $580 which will go towards the construction of a dry wood warehouse, designed to facilitate the rapid drying of the wood, which will produce a larger supply of workable wood. Oh, and another $20 for a radio, so these guys don´t have to work in mute silence all day long.

SANITATION

The first step in reducing water-borne illness is providing a safe water supply to the community. Fortunately, all of the communities I visited already possess local wells or rudimentary running water systems, but most still lack any type of sanitation system, which is why building latrines is so important. In order to learn more about this reality and provide a helping hand at the same time, I participated in a five-day development project that will eventually provide six communities with outhouses for each family. [So, if anyone has any toilet-related questions, now is the time to ask...] Constructing these specially-designed latrines is especially important, as these “dry toilets” eliminate standing water, which is a breeding ground for disease-spreading mosquitoes. What also interested me about this project is the process of involving six local communities: three representatives (including the Community Association President and a village elder) were present for the workshop, which was carried out in a small but centrally-located community. Engineers from the national health board were there to administer the instructions and everyone helped in mixing the cement, digging the holes, etc. I would not call the work more fun than working at the baseball stadiums, but certainly more important. The $580 I donated will go towards funding similar projects in the coming year, so that more communities will be saved from the spread of preventable communicable diseases. Basic sanitation, a reality we all take for granted, should not be a luxury item.

EDUCATION

Due to these communities´ isolation, federal services – if they exist at all – are lacking in scope. This is especially true in terms of education, as most schools here only go up to the fourth grade. Only 7.5% of the caboclo kids in this region have access to high school, which forces half of the kids to migrate to cities in search of educational opportunities or work. In additon to depriving the community of able-bodied workers and leaders, this exodus threatens the traditional culture that is passed on orally through the generations. Fortunately, a few communities have banded together to finance their own supplemental schools to provide a extra years of education for their children. I had the good fortune of visiting one such school which finances a separate classroom for fifth, sixth and seventh graders, extending these children´s education for three additional years. This multi-grade approach (a logistical necessity, due to the small number of students and limited resources) captivated me, as I too spent three years of elementary school is such a multi-level classroom. The school´s multi-disciplinary approach uses art, play and communication to creates a stimulating environment to pique the kids´ interest in learning, quite different from the dry, boring approach of the public schools. I was so impressed with the staff´s dedication and cultivation of an inter-community forum to work with other villages facing the same challenge that I donated $580 to provide much-needed materials such as school books and art supplies.

Though each of these projects are addressing recognized needs, there are plenty of other issues that demand attention. It was obvious through my visit for example that there is a lack of family planning. As long as family sizes continue to increase unababted, these communities will exhaust their natural resources which will force them to decimate the forest in order to guarantee their own survival. Given alternatives, there is no reason to think the Amazon rain forest cannot be saved, but without a means of income and basic health, the fragile eco-systems here will suffer as a result. Guaranteeing the environmental survival of the Amazon is the world´s responsibility, but it starts with the people who have lived here for centuries. Walking through the rainforest with some of the local kids in search of tropical fruit, I was impressed to watch them identify nearly every plant, explaining to me what each can be used for. I hope their mutually beneficial relationship with their environment continues for centuries to come and I thank all of my donors for allowing me to immerse myself in this region´s reality and improving the lives of their wonderful people in the process.