http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lj6YWk4Vvws

How does a 14th century King of Mali relate to the modern plight of the handicapped people in this destitute West African country?

Sandiata Keita’s greatness was predicted before his birth when a witch-doctor prophesized that Sogolan (a particularly ugly princess) would beget the greatest king in the world. That prediction seemed pretty implausible when baby Soundiata was born with paralysis in both legs. Miraculously though, at the ripe age of nine, he gained the use of his legs and soon developed into a muscular hunter. Then, just five years after becoming ruler of his small Malinké state in 1230, the brave warrior confronted and vanquished his daunted foe, the leader of the huge vassal state that had oppressed his people for centuries. King Soundiata went on to unite an alliance of independent chiefdoms into the venerated Mali Empire, which would later grow into a sprawling kingdom with riches coming from caravan trade of gold and salt from Timbuktu and beyond.

Jump to 2009 – Mopti , Mali. As I stroll through the bustling Mopti market, weaving amongst balls of dried onions, baskets of dried fish and loads of bananas (see related video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oTmlNVTtx2I), I see a physically-challenged (which I will refer to as handicapped as that is the accepted term here) man shuffling along the dirty streets, using his arms to pull himself around. Despite the uplifting story of Sandiata, the King of Kings, most handicapped people here in Mali cannot count on such a glorious transformation; most cannot even afford to eat one meal a day. Though I have seen the sight plenty of times throughout the developing world, it is always troubling to watch people shuffle around the city on their hands and knees. Walking next to them or standing above them, I appreciate every walking step I take, as whatever problems I may have pale in comparison.

Mali is ranked one of the poorest countries in the world, with an average annual income of $470. Scraping out a living is a challenge for nearly all of the country’s twelve million inhabitants, which is why nearly 75% of Malians live below the poverty line. Given these economic challenges, imagine the prospect faced by the country’s million-plus handicapped people. There are no anti-discriminatory laws here, no sidewalks and no government programs to provide them with social relief. They are literally left to fend for themselves.

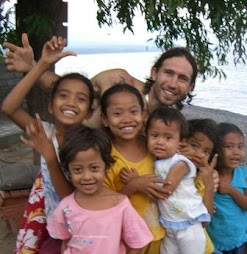

Seeing these people struggling to dodge cars, motorbikes and goats on the chaotic city streets tugged at my heartstrings. Later, as I played with some kids in front of Mopti’s ornate mud-brick mosque, I met a man in a bicycle wheelchair, which is the only way these people can get through the hectic streets here. He told me about the Association for the Handicapped of Mopti which had changed his life. I searched out the AHM center and arrived to find two men sitting under the shade of a neem tree. I introduced myself and asked to speak to the director, at which point a man with two lame legs shuffled through the doorway, ushering me forward with a warm smile. To my surprise, he opened the door to the office, pulled himself up onto the chair and presented his hand to me, formally presenting himself as Mohamed Cisse, Director of AHM. Seeing him sit there with pride and stature, having witnessed his sudden transformation from relaxed mode to focused Director mode, I could not help but think back to King Soundiata.

Bara Tamboura, the President of ADHM and Mohamed Cisse are two of the local heroes I often rave about; these are the people that recognize a need in their community and then mobilize their forces and amass whatever resources they can in order to make a difference. They are my inspiration. The raison d’etre of the organization is to provide the handicapped people here with a means of generating their own income. The “Help Them Help Themselves” mantra is perfectly embodied here; as each of these man and women come here everyday to work diligently. Though they started from nothing, the association has evolved into a huge workshop where members make shoes, jewelry, belts, clothes, soap, etc. These products are then sold at the market with the proceeds split equally to all; this communal philosophy carries over into everyday interactions, as members feel a strong sense of community with each other.

“Before the association,” Asitsa, a matronly woman with colourful rich fabric and a deformed leg tells me, “I felt a lot of shame because of my condition, but since coming here I have overcome the complex and accept my fate as just another challenge to face.” Other members told me how important the remedial education classes are, as many of them were ostracized from their communities or had no means of getting to and from school as children. After confirming the credibility of ADHM with a US-based non-governmental organization that will begin working with them this year, I searched for the most effective way to help. After speaking with the Director, I learned that although there are over 200 members in the group, only 55 of them can make it to the center, as the others do not have the transportation (i.e. wheelchairs) to get there. I asked Bara to bring in some of the recipients in need of a wheelchair and later that day, once we were all seated on the ground, I explained the nature of my visit and announced that on behalf of 100 Friends and all of my wonderful donors, I would like to purchase two wheelchair bicycles and pay for the repairs of four others that lie in disrepair. Ear-to-ear smiles of unbridled joy erupted amongst all present. “You have no idea how much this will change my life,” Abdullah told me as he tried kissing my hand. I told him it is only through the generous donations of my friends in America and beyond (thanks to my first donation from Nawelle in France !) that allowed me to provide him his dream. He smiled as he said, “Well, tell them tanks for me - they have given me the biggest present of my life.” Enough said.

But I did not want to stop there, as these peoples’ perseverance to overcome their disabilities truly inspires me, so I did some research and discovered another way to positively affect these marginalized of the marginalized: by working with Trickle Up, a very highly-accredited US-based non-governmental organization (NGO) that delivers small grants to very poor micro-entrepreneurs around the world, with wonderful success here in Mali. It just so happens they assist the handicapped association of the nearby town of Sevaré , allowing individuals and entire families to rise from the lowest rungs of poverty. Each recipient receives business training to learn about entrepreneurship, marketing and balancing their books. Trickle Up’s local professionals then help them devise and develop business plans that will earn their families an income. Next, they are then provided with a seed capital grant of $100 to start their business. In the case of one gentleman I met, this money went towards buying the supplies needed to repair stereo equipment. For others, this seed grant can purchase a sewing machine. Trickle Up also introduces these micro-entrepreneurs to savings institutions to allow for sustainable growth and an emergency fund. With our $500 contribution towards the Sevaré Handicapped Organization (GPHA), 100 Friends will be sponsoring five new micro-entrepreneurs in their business ventures. That’s five families of handicapped people that will be able to earn a living and rise above the $1 a day income they have been sentenced to by their unfortunate condition.

Sure, the handicapped people we have helped here in Mali may not go on to become Kings, but meeting the directors of these two associations and seeing the industriousness of its members, it is obvious there is hope for a brighter future. Without your help, these people would be shuffling around on the streets begging for spare change, but today they are proud members of society, working hard and smiling the whole day through.

No comments:

Post a Comment