http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n8v-g4uM7Kc

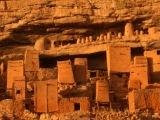

Life here in the desert is a daily struggle to survive. It is hard for many of us to comprehend such a tenuous grip on life, but it is true. I have spent the last few weeks in, or on the fringes of the Sahara Desert. Here in the transitional region known as the Sahel that covers over a million square miles, I can see that people here are locked into a daily struggle to survive – it is man against nature on a grand stage and every waking moment is a vigilant battle to extract enough water and food to see tomorrow. Sure, the sand dunes, camels and sunsets here are breath-taking, but beneath the surreal sandscapes, there exists a much more troubling reality: the desert is expanding its dry grasp on the region, forcing people to flee from their communities and drastically altering their lifestyle. In this punishing terrain; water is the key to life and supercedes everything else. There is a battle going on between man and nature here in the Sahel; the desert is winning.

While in Mali, I ventured north of Timbuktu into the heart of the Sahara, a place where majestic sand dunes speak stories of colonial explorers in search of legendary riches. Riding on camelback, I spent time with the Tuareg people, a nomadic desert tribe that used to control the caravan routes in days of yore. But the Tuareg lifestyle and the rich culture that goes along with that is in dire jeopardy, as climate change is forcing them to adapt to the sudden water shortages plaguing their ancestral homeland. While sipping green tea in a tiny village called Essoukane, my Tuareg friends told me that their local wells have dried up, so people come on camelback from surrounding villages to get water from a single UNICEF truck that arrives once a month. Many though, are not so lucky.

Here in Mauritania , the desert’s land grab is killing people in its wake. 75% desert, this country has always had to deal with a harsh arid climate, but in the last forty years, drought and deforestation have compounded the problem. The northern half of Mauritania is pure Sahara, while the southern half is more wooded, but the desert has been inching further and further south every year. Driving through Mauritania, I can see the desertification firsthand; in several villages, family homes have been invaded and taken over by the sand dunes, blown into place by the harmattan winds that are especially strong this time of year. (Lunch break everybody: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n8v-g4uM7Kc)

The blowing sand forms new dunes, masks my vision in a dusty cloud and pervades every pore of my body. While in the east of the country, I met American Peace Corps volunteers that are helping re-forest small tracts of land, but the scale of desertification is immense. Sadly, this process is a vicious circle: drought forces people to settle in more pastoral areas, which increases demand for scarce water and compels families to cut down trees to feed their animals, earn a living and cook their food. This in turn creates competition for water and resources which exacerbates the poverty and ultimately forces people to flee the countryside altogether.

The lack of water and income forces rural families towards the cities, in this case Nouakchott, the capitol city of uncontrolled urban growth. This city was built for a population of 15,000 back in 1959, but today it is home to 600,000 - and growing at a clip of over 5% per year! Malnutrition here is rampant, as are respiratory and water-borne diseases. Without any housing, migrants are forced to live in tents on the city’s outskirts. The government is having a tough time dealing with this climate change, as 14% of the annual budget ($192 million) is swallowed up by environmental degradation. Seeing a family of eight huddled into a tent, cooking meager meals over a small fire is heart-wrenching, especially considering the fact that just a few years ago, many of these families were living in their ancestral communities, earning a stable living from their pastoralist lifestyle.

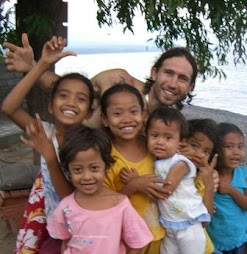

With the help of my translator, a Captain in the Mauritanian Army familiar with these nighborhoods, I ventured into one of these desert shanty-towns to deliver some desperately-needed funds to five families in especially-vulnerable positions. Each of the families’ situations is just as pressing as the next: there is the case of the mother and her children deserted by her husband, leaving her with eight hungry mouths to feed; she buys a kilo of rice and sells it off in parcels to neighbors, netting a dollar profit. Then there is the nine year-old girl with a terrible foot infection, whose parents do not have enough money to send her to the hospital.

I could go on and on – the widow left with four kids, the elderly woman reduced to begging for scraps, the man who labors daily at the fish market for twelve hours a day to earn $2 to feed his family of six...Hearing their stories, it becomes obvious each of these families have been victimized by the encroaching desert; try telling them climate change is not real! They speak of their days in the desert as though they were glory days; though their existence out there was always a bit precarious, at least they knew they could put food on the table.

It is easy to fall into a sandy swoon with romantic images of the desert, but we cannot forget the raw truth : the desert is a harsh killer that swallows everything in its path. Seeing these families battling for survival, I reflect on the problems many of us are faced with and realize once again, that they pale in comparison. I wish everyone out there could see the faces of joy and relief when presented with this money to provide food, medical care and school supplies to these families that have been displaced by the desert’s unrelenting expansion.