http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h-AbzvIxr88

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h-AbzvIxr88(VIDEO UPDATE)

AFRICAN FIELD REPORT #2: Alleviating Infant Mortality in Guinea-Bissau

The Milkman Cometh!

You ever wonder what ever happened to the baby in the bed next to you at the

nursery? Did he go on to become a doctor? Is she a race-car driver?

It wasn’t until I landed here in Guinea-Bissau, a tiny impoverished

nation in West Africa that I pondered this question. You see, Guinea-Bissau and

I share a common bond, but I didn’t discover this until I scoured the streets

of the capitol city Bissau for an affordable hotel room. Since there are no

tourists whatsoever in this undeveloped country of one and a half million

people, the only hotels exist to cater to foreign development workers whose

organizations pay their expensive hotel bills. After trudging through the dusty

streets for an hour with my backpack getting heavier by the minute, I was told

about a somewhat-affordable place on Avenida 12 de Setembro. Ecstatic to

finally speak Portuguese in Africa, I asked the importance of this date, for I

assumed it had not been named in honor of my birthday. I was told that September 12, 1974 is Guinea-Bissau’s

independence was recognized by Portugal.

But despite our common birthday, our destinies could not be more different. I

was conceived out of the pure love of two wonderful parents. Sure, I had a bit

of a tumultuous delivery; my mother still complains about my two-week late

arrival, but in the midst of placental bliss, I must not have gotten the memo

telling me my nine months were up. But upon my arrival, I received excellent

medical care, nourishing breast milk and a happy home.

Guinea-Bissau, on the other hand, was born out of centuries of conflict. For

two hundred years, this region was home to the torturous slave trade between the

Portuguese empire and the African tribes that thrived from this shameful

practice. This human commerce was so profitable that the region was coined

“The Slave Coast” and colonized by the Portuguese in the eighteenth century.

After hundreds of years under the yoke of colonialism, an independence movement

was born in 1956, but nearly twenty years of armed conflict would take place

before independence was granted. Shortly before its birth, its founding father

Amilcar Cabral was assassinated. When Guinea-Bissau was officially born, the

Portuguese left the country en masse, and what remained was a struggling economy

beset with political instability and under-funded and inefficient health and

educational systems.

Since our shared birthday, while I have received nourishing food, wonderful

schooling and a healthy upbringing, Guinea-Bissau has been wracked by uprisings,

coups and a crippling civil war in 1998. (As a sidenote: I visited a British

organization that is still clearing undetonated ammunition from the countryside

here that has remains from the civil war; farmers and children still lose

limbs and lives to these unexploded weapons). While many countries have enjoyed

economic expansion, Guinea-Bissau has been plagued by debt and a lack of social

services; today, roughly a quarter of kids here complete the sixth grade and

it’s per capita income hovers around $600 a year. To make matters worse, this

country has become a transit point for South American cocaine shipments to

Europe, with many government officials involved in the trafficking, which

generates ten times the country’s national income.

Arriving in complete darkness in the absence of streetlights while crammed into

a station-wagon with nine other passengers, it was immediately obvious this

country is beset with problems. Besides the fact there was a failed coup

attempt six days before my arrival when a military faction invaded the

presidential palace, there is virtually no running water in the entire country

and only electricity in the capitol city of Bissau. Even here though, power is

spotty at best, as I learned while trying in vain to sleep in a sweaty bed.

While in the country’s second largest city, Bafata, I learned there is no

internet available in town - anywhere. Imagine Los Angeles without a single

internet connection.

But what is especially troubling about this country are the horrific health

conditions. The male life expectancy in the US is 75 years, but only 45 here in

Guinea-Bissau, so while I consider myself enjoying the prime of my life, that

baby in the crib next to me, if he were from Guinea-Bissau, would be only ten

years from his grave.

That got me thinking about the babies here in Bissau that are born into such a

fragile existence. In fact, Guinea-Bissau’s infant mortality rate ranks as

one of the highest in the world. Over eleven percent of babies born here do not

survive their first year of life and twenty percent of babies do not live to

celebrate their 5th birthday. Just think about that a second; imagine if every

child you gave birth to or knew had a 11% chance of dying before it’s first

birthday. It’s a startling statistic. As a result, many babies here are not

even named until six months after their birth, so as to avoid an emotional

attachment with a child with such a tenuous lease on life. While funerals for

old members of the community are very somber events, the deaths of young babies

do not warrant big ceremonies. The main causes of infant mortality are malaria,

acute respiratory infections, malnutrition and water-borne diseases.

Another related health problem for babies and the entire population is AIDS.

While the nation’s HIV rate is much lower than many other African countries,

what is especially troubling is the “vertical transmission” rate from HIV+

mothers to their babies, a figure that stands at about 25%. After researching

this problem, I learned that by treating the mother with a drug called Retrovir

during pregnancy and delivery and then administering the newborn with the same

drug for the first six months of its life can reduce to rate of transmission to

2.5%!

In the process of searching out a local project that addresses this need, I

visited with officials from international health organizations, the European

Commission and the Maternity Ward at the government hospital (which was a very

troubling experience). Several people I spoke with in Bissau

raved about the same project: Clinica Ceu e Terra, which was founded in 2001 by

a Cuban doctor who has been working here for twenty years. This clinic (which

translates to Sky and Earth Clinic) offers free services to more than 2,000 HIV+

women in order to prevent the vertical transmission of the virus to their

babies. Without this clinic, there is no chance these women would be able to

afford the Retrovir or the powdered milk to feed their babies. 25% of these

children (500 babies) would be sentenced to a life with HIV, but thanks to the

wonderful work of Ceu e Terra, only 2.5% (50 of them) will inherit the virus.

That’s 450 prosperous lives spared. Those are the kind of results I look for

before supporting a project!

Speaking with the director of the clinic, I offered to help on behalf of 100

Friends, at which point she let out a huge sigh of relief as she explained that

one of the clinic’s foreign donors had recently re-allocated its resources,

leaving her with a shortage of the fortified powdered milk the mothers feed

their babies. I went directly to the supplier and purchased $600 worth of

product, tossed it in the trunk of a taxi and returned an hour later as the

Milkman Extraordinaire. I also sought out two mothers that are in especially

dire straits and provided each with $60(over a months wages here) to spend on food for their babies, as

they are currently facing malnutrition.

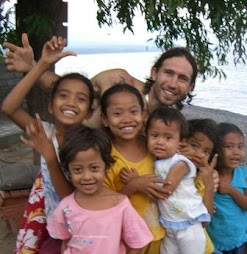

As I held baby Mamadou in my arms, it saddened me to reflect the uphill battle she faces.

I thought back to my own days as a newborn and more than ever, I realize just how blessed I have been. I only hope that

with the help of clinics like this and through the generous donations of people

like you, Mamadou will live a happy, productive life in this challenging land of

limited opportunity.

No comments:

Post a Comment