The tight alleyway wound its way through a labyrinth of concrete. Everywhere I looked narrow stairways led into dark caverns. My path dipped and veered, rose and fell, winding left, then right, up then down. Electrical wire hung haphazardly from low-hanging poles and the never-ending network of plastic water pipes all seemed to be interconnected. There was no method to the madness – it was a hilly conurbation completely devoid of urban planning. I felt like I was walking through a dream world, but my heart raced with a vigor that only imminent danger can bring, keeping me conscious of the reality at hand: I was walking through hostile territory under the cover of darkness. But somehow, this ethereal world captivated me, as though I was hiking through that optical illusion where all the stairs that go up somehow lead to the stairs going down, leaving the viewer trapped in a vicious visual circle. The sinuous path twisted under houses whose only space to expand was over the alley, creating a concrete tunnel and obscuring the sun, or in this case, the moonlight. Purely surreal. I continued climbing through this boundless three-dimensional maze and finally emerged onto a main street. I surfaced from the shadows and found myself face-to-face with an assault rifle. Its owner wore a flak jacket, loaded with an extra clip, but no uniform. He may be a soldier, but his army wears no badges. To quote Treasure of Sierra Madre, a famous film from the 40s, "Badges? We don’t need no stinking badges!"

For those worried about my location, no, I am not describing Fallujah, though my environs are reminiscent of many Middle Eastern medinahs I have wandered aimlessly. The gun-wielding kid before me is not an insurgent, a freedom-fighter or a revolutionary. He is a drug-dealer. I met him, and many like him, in Rocinha, a favela in Rio de Janeiro. With over 250,000 inhabitants, its Latin America’s largest shanty-town, though it is more of a city than a favela, as it has a thriving culture, running water and electricity. It also has a murder rate higher than many of the world’s war zones.

Most residents of Rio do everything in their power to steer clear of Rocinha and insist anyone that visits is risking their life. But I have friends that live here and since my immersive instincts have taught me to experience a place before I judge it, I decided to stay for a while. What I discovered is a surprisingly safe spot that offers an almost-addictive sense of adventure. No wonder thousands of Rocinha’s residents wouldn’t want to live anywhere else...

Last year when I was living in Rio, my first "visit" to Rocinha had been from the air when I hang-glided from a nearby mountain. As I soared with the sea hawks looking down upon the bustle of activity below, I took pride in the fact that I had overcome an irrational fear. Many desist from leaping off mountains for safety concerns, but my brave mother and I had made the jump. On this second visit, yes, there was a higher level of danger as Rocinha can be a perilous place. Last year, a war erupted with Vidigal, the neighboring favela; it was a bloody episode and many were killed. And yes, tensions are once again on the rise as the whiz of pistol and machine gun fire becomes more frequent. But for the most part, this is controlled violence, carried out by professional soldiers on virtual battlegrounds for purely business-related reasons. Everyday life in Rocinha is safe, which is unexpected considering the complete absence of police. As in most favelas, the police are distrusted and disliked; they only enter in SWAT teams when they want to apprehend (or more often, collect a bribe from) a high-ranking drug trafficker. It is the drug cartel that maintains order in the favela and though they rule with an iron fist, the petty crime rate here is lower than anywhere else in the city. Though the wrath of vigilante justice may be brutal and the "trials" short, people know that theft, rape and assault are punishable by beatings or death. It’s an irrevocable truth that keeps people in line.

Rocinha is a world of its own with a distinct culture. Many of the original inhabitants are nordestinos that arrived as early as the 60’s, fleeing the drought and poverty of the Northeast in order to search out work in Rio. Many, such as Marcelo, the proud grandfather that lives here with his huge family, have been here for three generations. Taking me to his rooftop to display his expansive view of the favela below, I sense his deep pride in Rocinha. Though most would never even visit, he refuses to leave. From his vista, he describes the geography of the favela, which is built on a huge hill overlooking some of Rio’s most wealthy neighborhoods. Down below, the bustle is greatest, as four-story apartment buildings have been built where the highway meets the favela. Looking up at night from the street below, where Rio melds into Rocinha, the favela glows with lights that resemble stars, as though its own universe, which isn’t too far from the truth…

My first day in Rocinha was a bit strange, as I felt like I was re-enacting the now-famous favela-based movie City Of God. Anyone will recall the opening scene with the knife being sharpened, while the doomed chicken ponders its impending fate. This was the exact scene as my friends and I had decided to create a feast of our own, our savage dinner preparations somehow mirroring our brutal surroundings. Later that evening, after the "sacrifice," we went to a party in a neighborhood called Laborario, which is perched on the hilltop where the favela spreads even higher above the city. Though blessed with breath-taking views of Rio (spread out like a satellite map below us), I felt like I was in a quaint mountain town, as we hiked through green mountainous trails complete with monkeys and mango trees. It was a steep half-hour hike from the bottom, but much more open and expansive than the cramped conditions down below. As we descended, my peaceful mood was shattered by gunfire. Since I was walking with residents, I watched their reaction for clues. No one displayed any concern, so I asked if those were fogueteiros, the child lookouts that fire off firecrackers to alert the drug kingpins of any incursion by the police or rival drug gangs.

"No, that was a Kaleshnikov," my friend calmly replied. "They’re firing down from the mountain between here and Vidigal. Not a big deal," I was assured. We continued down the narrow paths until we came to Estrada da Gavea, the main drag of Rocinha and immediately noticed that something was going down. A phalanx of men with submachine-guns and flak jackets paraded through the streets, as though they were guarding a president. Though the sight of these massive guns was a bit unsettling, I knew I was in no immediate danger. My presence meant nothing to these soldiers; I was just another face on the street. We continued down the street and came to a spot where more soldiers had congregated. They were communicating by walkie-talkie and had paused, as though awaiting orders. They resembled a unit of ground troops, but their surroundings were so commonplace (a hot-dog stand and a bar blasting music) that it was hard to imagine they were actually engaged in warfare. Right next to them, a man was selling wheels of farm cheese from the trunk of his car. Though most people that suddenly find themselves surrounded by such heavy artillery would run (or at least keep as quiet as possible), the cheese-seller didn’t even blink. He continued yelling his vending chant, "Quejo mineiro! Bom precio!" It was his cool demeanor and the lack of panic (or even worry) on the faces of those around me that made me realize that what looked like a dangerous situation was just a mundane moment of daily life.

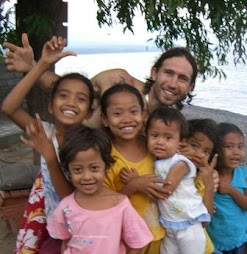

When I left the favela the next day to take care of some business in Rio proper, I longed to return to Rocinha. Though some would call it recklessness, I felt myself drawn to something greater. Rocinha represents the rawness of real life. Its residents range from garbage-pickers to drug kingpins. In the days to come, I hung out with both. We sipped beer on the street, hung out with great-grandmothers and tiny babies and cruised from party to party, jumping on the back of motorcycles, dancing in sweaty clubs, eating greasy food and ogling at beautiful girls. Though I may write guidebooks, I find myself drawn to the places that don’t get mentioned. Call me the accidental tourist. My initial reaction may have been one of surrealism, as I wound through a maze of concrete and electrical wires, but getting to know the people and the mentality of the favela, I came to realize that Rocinha represents a reality few of us can fathom and incredibly, a reality I find hard to resist.

For those worried about my location, no, I am not describing Fallujah, though my environs are reminiscent of many Middle Eastern medinahs I have wandered aimlessly. The gun-wielding kid before me is not an insurgent, a freedom-fighter or a revolutionary. He is a drug-dealer. I met him, and many like him, in Rocinha, a favela in Rio de Janeiro. With over 250,000 inhabitants, its Latin America’s largest shanty-town, though it is more of a city than a favela, as it has a thriving culture, running water and electricity. It also has a murder rate higher than many of the world’s war zones.

Most residents of Rio do everything in their power to steer clear of Rocinha and insist anyone that visits is risking their life. But I have friends that live here and since my immersive instincts have taught me to experience a place before I judge it, I decided to stay for a while. What I discovered is a surprisingly safe spot that offers an almost-addictive sense of adventure. No wonder thousands of Rocinha’s residents wouldn’t want to live anywhere else...

Last year when I was living in Rio, my first "visit" to Rocinha had been from the air when I hang-glided from a nearby mountain. As I soared with the sea hawks looking down upon the bustle of activity below, I took pride in the fact that I had overcome an irrational fear. Many desist from leaping off mountains for safety concerns, but my brave mother and I had made the jump. On this second visit, yes, there was a higher level of danger as Rocinha can be a perilous place. Last year, a war erupted with Vidigal, the neighboring favela; it was a bloody episode and many were killed. And yes, tensions are once again on the rise as the whiz of pistol and machine gun fire becomes more frequent. But for the most part, this is controlled violence, carried out by professional soldiers on virtual battlegrounds for purely business-related reasons. Everyday life in Rocinha is safe, which is unexpected considering the complete absence of police. As in most favelas, the police are distrusted and disliked; they only enter in SWAT teams when they want to apprehend (or more often, collect a bribe from) a high-ranking drug trafficker. It is the drug cartel that maintains order in the favela and though they rule with an iron fist, the petty crime rate here is lower than anywhere else in the city. Though the wrath of vigilante justice may be brutal and the "trials" short, people know that theft, rape and assault are punishable by beatings or death. It’s an irrevocable truth that keeps people in line.

Rocinha is a world of its own with a distinct culture. Many of the original inhabitants are nordestinos that arrived as early as the 60’s, fleeing the drought and poverty of the Northeast in order to search out work in Rio. Many, such as Marcelo, the proud grandfather that lives here with his huge family, have been here for three generations. Taking me to his rooftop to display his expansive view of the favela below, I sense his deep pride in Rocinha. Though most would never even visit, he refuses to leave. From his vista, he describes the geography of the favela, which is built on a huge hill overlooking some of Rio’s most wealthy neighborhoods. Down below, the bustle is greatest, as four-story apartment buildings have been built where the highway meets the favela. Looking up at night from the street below, where Rio melds into Rocinha, the favela glows with lights that resemble stars, as though its own universe, which isn’t too far from the truth…

My first day in Rocinha was a bit strange, as I felt like I was re-enacting the now-famous favela-based movie City Of God. Anyone will recall the opening scene with the knife being sharpened, while the doomed chicken ponders its impending fate. This was the exact scene as my friends and I had decided to create a feast of our own, our savage dinner preparations somehow mirroring our brutal surroundings. Later that evening, after the "sacrifice," we went to a party in a neighborhood called Laborario, which is perched on the hilltop where the favela spreads even higher above the city. Though blessed with breath-taking views of Rio (spread out like a satellite map below us), I felt like I was in a quaint mountain town, as we hiked through green mountainous trails complete with monkeys and mango trees. It was a steep half-hour hike from the bottom, but much more open and expansive than the cramped conditions down below. As we descended, my peaceful mood was shattered by gunfire. Since I was walking with residents, I watched their reaction for clues. No one displayed any concern, so I asked if those were fogueteiros, the child lookouts that fire off firecrackers to alert the drug kingpins of any incursion by the police or rival drug gangs.

"No, that was a Kaleshnikov," my friend calmly replied. "They’re firing down from the mountain between here and Vidigal. Not a big deal," I was assured. We continued down the narrow paths until we came to Estrada da Gavea, the main drag of Rocinha and immediately noticed that something was going down. A phalanx of men with submachine-guns and flak jackets paraded through the streets, as though they were guarding a president. Though the sight of these massive guns was a bit unsettling, I knew I was in no immediate danger. My presence meant nothing to these soldiers; I was just another face on the street. We continued down the street and came to a spot where more soldiers had congregated. They were communicating by walkie-talkie and had paused, as though awaiting orders. They resembled a unit of ground troops, but their surroundings were so commonplace (a hot-dog stand and a bar blasting music) that it was hard to imagine they were actually engaged in warfare. Right next to them, a man was selling wheels of farm cheese from the trunk of his car. Though most people that suddenly find themselves surrounded by such heavy artillery would run (or at least keep as quiet as possible), the cheese-seller didn’t even blink. He continued yelling his vending chant, "Quejo mineiro! Bom precio!" It was his cool demeanor and the lack of panic (or even worry) on the faces of those around me that made me realize that what looked like a dangerous situation was just a mundane moment of daily life.

When I left the favela the next day to take care of some business in Rio proper, I longed to return to Rocinha. Though some would call it recklessness, I felt myself drawn to something greater. Rocinha represents the rawness of real life. Its residents range from garbage-pickers to drug kingpins. In the days to come, I hung out with both. We sipped beer on the street, hung out with great-grandmothers and tiny babies and cruised from party to party, jumping on the back of motorcycles, dancing in sweaty clubs, eating greasy food and ogling at beautiful girls. Though I may write guidebooks, I find myself drawn to the places that don’t get mentioned. Call me the accidental tourist. My initial reaction may have been one of surrealism, as I wound through a maze of concrete and electrical wires, but getting to know the people and the mentality of the favela, I came to realize that Rocinha represents a reality few of us can fathom and incredibly, a reality I find hard to resist.

No comments:

Post a Comment